It is time for a new National Energy Policy to support a clean, modern energy system. The energy sector is the largest contributor to emissions of greenhouse gases that are causing climate change.[i] Consumers see rising prices for electricity and hear industry complaints about onerous regulations and government curtailment.[ii] Utility companies struggle to address reliability of service requirements and universal service standards even as data centers and AI applications add intense demands for electricity.[iii] Much of the focus on climate action involves shifting to electricity for buildings, transportation and even industry. If the country is to meet climate goals, the shift from burning coal, natural gas and petroleum for power generation must occur much more rapidly.[iv]

Transforming the nation’s energy system to one based on renewable and sustainable resources is a critical element in responding to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Unfortunately, practitioners in the renewable energy systems space currently encounter significant regulatory and institutional barriers to rapid and efficient implementation of new technologies and practices.[v] National energy policy is needed, including an update to the energy industry’s regulatory framework, to advance the modernization of our country’s electricity delivery system.

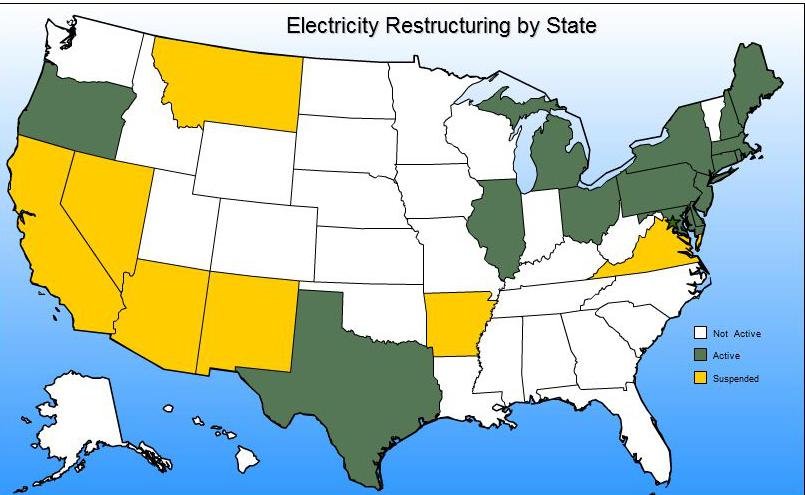

The current regulatory framework is built around centralized energy generation from utility monopolies that deliver electricity to customers residing across a wide geographical territory. Under the National Energy Act of 1992, partial deregulation of the nation’s electricity system took place, leaving a patchwork quilt of conditions in place across the country: 17 states are fully competitive with customer choice for electricity generation and gas supplies; 9 are deregulated for gas suppliers only; and 23 remain fully regulated for electricity and gas.

Data Source: US EPA https://www.epa.gov/greenpower/understanding-electricity-market-frameworks-policies

Modernizing the nation’s electrical grid system means moving away from this current model of centralized energy generation towards generating energy on site or nearer to the consumer. In this emerging, more distributed energy system, customers may also be generators of the power they consume, they may have on-site storage for all or part of their demand, and buildings can even become virtual power plants by generating excess electricity that can be shared with others in need of that energy. This empirically straightforward approach that is technically feasible, economically beneficial and widely available unfortunately faces enormous difficulties when put into practice. For example, in a Pittsburgh community three municipal buildings adjacent to each other – the volunteer fire department, public works garage and storage shed and emergency management service – cannot share a common battery storage installation or share the solar photovoltaic electricity generated on three of the four roofs because a “public way” divides the space, and the buildings are wired to three different distribution grids, but not to each other. The cost to re-wire was more than the cost of installing all of the solar arrays! There is no standard interconnection protocol, and no tariff that fairly allocates costs and benefits. Grid-interactive Efficient Buildings are technically feasible.[i],[ii] We need to clear the regulatory hurdles to expand deployment to make buildings perform as virtual power plants.

Manufacturers and large-scale energy users explore the increasing benefits of co-generation, combined heat and power operations, and on-site storage. New high energy intensity operations like data centers and AI operations could benefit from co-locating efficient power generation on site and piping excess heat to neighboring facilities in need of that heat.[iii] A new regulatory system that accommodates customer generation can accelerate the necessary large- scale advance of renewable energy systems. However, there are few models for regulatory interface among producers and users of steam plus electricity, or waste heat and power. Such arrangements usually involve complicated business negotiations and are unique to each project. If distributed energy systems are to become mainstream and accessible to a multitude of energy system configurations, a regulatory system that defines the relationships and possibly new utility services and functions can expedite and streamline such transactions.

Major existing regulatory and institutional barriers

The regulatory system has accumulated policies and practices over decades, proving resistant to change even as technology advances have accelerated.[iv] The most significant regulatory and institutional barriers to modernization include:

- Policy fragmentation across jurisdictions. Federal, state, and local jurisdictions have differing and sometimes conflicting requirements making national markets difficult to pursue. To correct policy fragmentation, we need more standardization of methods and processes in a systems-oriented approach to regulatory infrastructure modernization.

- Permitting complexity. Multiple agencies require differing and overlapping permit requirements, poorly sequenced with no clear path among multiple authorities. Grid integration challenges face transmission and distribution capacity constraints, as well as interconnection and Regional Transmission Organization [AW1] market rules, that pose barriers to renewable energy implementation, in modern utility operations, and impede net-zero greenhouse gas emissions outcomes.

- Grid integration challenges. Utility systems have capacity constraints as well as a lack of interconnection infrastructure to support “two-way traffic” among customer/generators with or without on-site storage.

- Lack of uniformly recognized guidelines for RECs. There is no standard framework for defining Renewable Energy Certification (REC) credits that track and verify demand reduction or customer renewable energy generation across jurisdictions. Different states, and sometimes different utilities within states, have differing definitions, pricing and verification methods applied to RECs.

- Erratic and unstable incentives. Production tax credits, investment tax credits, subsidies, land use allocations for federal land are subject to change with budget cycles unless established in law. The unstable incentives send the wrong pricing signals to the economy and foster inefficient choices for decades, impeding the progress to market transformation and decarbonization.

The current electricity system was designed for one-way flow of electricity from central power generation stations to distant residential, commercial and industrial customers. Now, several categories of customers also have the opportunity to generate electricity, and send it back into the electric grid. The electricity system, and the rules that govern it , are not designed for this two-way travel of electrons. In addition, standard interconnection procedures are needed for 1) virtual community power plants with or without storage; 2) standards regarding energy storage, steam/heat distribution or sale from combined heat and power operations, whether by a utility or a non-regulated entity; and 3) demand side management tied to time of use cost savings.[v] The integration of such services into the electric grid would benefit from innovations in communication technology and AI for real-time synchronization of both supply and demand side resources over daily and seasonal cycles.[vi] Many states have explored various approaches to regulatory incentives for renewable energy which provides a good place to begin to assemble the best practices across the country.[vii]

Opportunity for legislative action on national energy policy:

Three federal legislative initiatives will be pending over the next two years and could be legislative vehicles for the adoption of a national energy policy:

- Reauthorization of Tax Reform Act of 2017

- Regulatory Modernization and Permitting (especially shortening timelines)

- Funding decarbonization and electrification initiatives from the Inflation Reduction Act

- Budget authorization for programs under the Bipartisan Infrastructure and Jobs act and the Inflation Reduction Act.

Updating a National Energy Policy to address the urgency of climate action as well as the complexity imposed by the accumulated regulatory fabric of past decades offers a unique opportunity to a new Administration. It is important for the next President to address a forward-looking energy policy that empowers and accelerates the critically necessary modernization of the energy system. Every citizen is affected every day by how cost-efficient, safe and reliable the energy system serves daily needs. Resolving the regulatory quagmire will pave the way for a clean and sustainable energy future.

[i] National Association of Regulated Utility Commissioners and National Association of State Energy Officials https://www.naseo.org/issues/buildings/naseo-naruc-geb-working-group

[ii] National GEB Roadmap: U.S. DOE, A National Roadmap for Grid-interactive Efficient Buildings (May 2021)

[iii] U.S. DOE. Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Connected Communities presentation December 2, 2021.https://www.naseo.org/data/sites/1/documents/tk-news/connected-communities-for-geb-working-group.pdf

[iv] Seetharaman, Krishna Moorthy, Nitin Patwa, Saravanan, and Yash Gupta. Breaking barriers in deployment of renewable energy. Heliyon 5 (2019) e01166. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019. e01166

[v] G. Olabi, Khaled Alsaid, Khaled Obaideen, Mohammad Ali Abdelkareem, Hegazy Rezek, Tabbi Wilberforce, Hussein M. Maghrabi, Enas Taha Sayed. Renewable Energy Systems: Comparisons, challenges and barriers, sustainability indicators, and the contribution to UN sustainable development goals. International Journal of Thermofluids. 20(2023) 100498. www.sciencedirect.com/journal/international-journal-of-thermofluids

[vi] NASEO, “Demand Flexibility and Grid-interactive Efficient Buildings 101” (September 2022) and “Grid-interactive Efficient Buildings: State Briefing Paper” (October 2019)

[vii] Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency. https://www.dsireusa.org

[AW1]Spell out acronyms

[i] United States Environmental Protection Agency. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Total U. S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector in 2022. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions%20Accessed%20September%2022 Accessed September 21,2024.

[ii] Robert Walton. “State Officials Blame Federal Regulators for Higher Energy Prices: ‘Consumers are getting hurt!’” Utility Dive. February 15, 2024. https://www.utilitydive.com/news/state-officials-blame-federal-policy-higher-energy-prices-EPA/707608/ Accessed September 20, 2024.

[iii] North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), Electricity Supply and Demand Data, 2023; Energy Information Administration (EIA) Monthly Energy Review; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) Pathways to 100% Clean Electricity, 2022. Note that electricity demand includes transmission losses and direct use. https://www.energy.gov/policy/articles/clean-energy-resources-meet-data-center-electricity-demand Accessed September 20, 2024.

[iv] Simon Black, Ian Perry, Nate Vernon-Lin. Fossil Fuel Subsidies Surged to $7 Trillion. International Monetary Fund Blog. August 24, 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/08/24/fossil-fuel-subsidies-surged-to-record-7-trillion

[v] Enerdatics. Addressing Policy and Regulatory Challenges in Renewable Energy Projects. July 6, 2023. https://enerdatics.com/blog/addressing-policy-and-regulatory-challenges-in-renewable-energy-projects/ Accessed September 20, 2024.